Chapter 1: Pirates and Promises

The Mediterranean in the first century BCE wasn’t just blue seas and sunshine. It was crawling with pirates. They raided merchant ships, captured aristocrats, and held them for ransom — the ancient world’s equivalent of high-seas kidnappers with a taste for quick money.

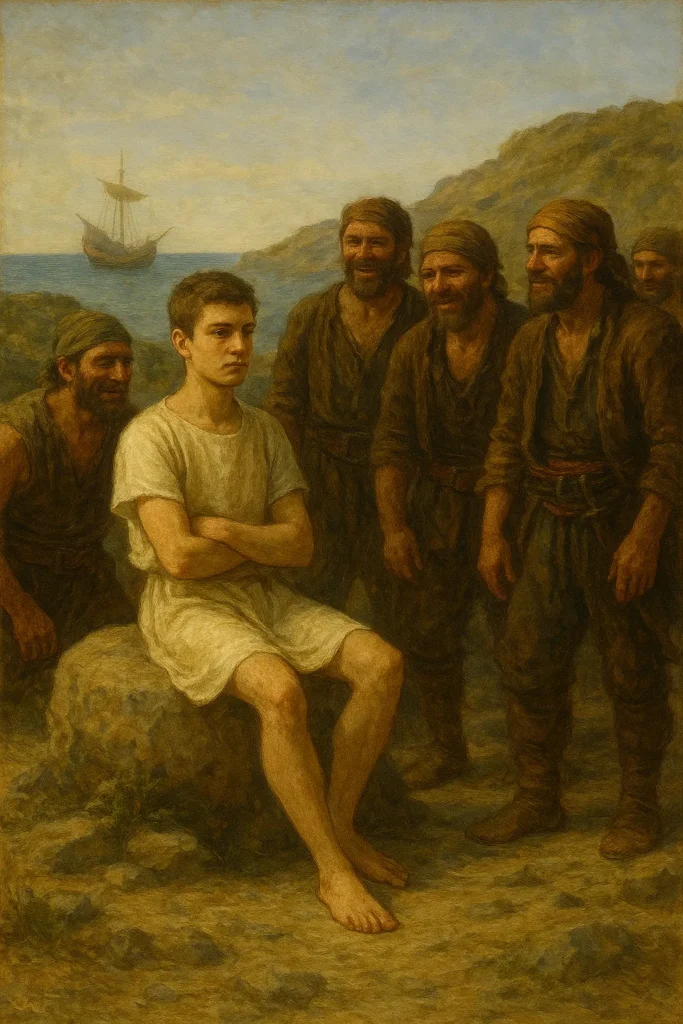

Into this world sails a young Julius Caesar, about twenty-five years old, handsome, ambitious, and on his way to study in Rhodes. He’s no general yet, no dictator, not even a particularly powerful politician. But he already carries himself with a certain aura, as if the universe has whispered to him: you are destined for more.

That’s when it happens. A band of Cilician pirates boards his ship and takes him hostage. For most Romans, this would have been humiliating. For Caesar, it became an opportunity to demonstrate what kind of man he was.

The pirates demanded 20 talents of silver for his release — a huge sum, but Caesar was outraged. Not because it was too much. Because it was too little.

“You clearly don’t know who you’ve captured,” he reportedly scoffed. “I am worth at least fifty talents.”

Imagine it: the prisoner negotiating for a higher ransom. And the pirates, amused, agreed.

“Caesar was ambitious, but with an ambition that seemed born not of vanity but of destiny.”— Napoleon Bonaparte, comparing himself to Caesar.

For the next 38 days, Caesar lived in their camp. But he refused to act the part of captive. Instead, he behaved as if he were the host and they were his rowdy guests. He joined their games, read them poetry, and gave speeches. When they failed to applaud enough, he scolded them for their poor taste. At night, when laughter died down, he would casually remind them: “When I’m free, I will come back and crucify every one of you.”

The pirates laughed. How could this cocky young Roman possibly make good on such a threat?

But Caesar wasn’t joking.

When his ransom was finally paid, he was released. Most men would have hurried home, grateful to be alive. Caesar raised a fleet, sailed straight back, and caught the pirates still lounging in their camp. True to his word, he had them crucified along the coast. Some sources say he ordered their throats cut first, a “merciful” gesture to shorten their suffering.

This wasn’t just a quirky episode. It revealed something essential about Caesar: his unshakable self-belief. Even when outnumbered, chained, and mocked, he radiated authority. Even as a captive, he acted like a ruler. And when he made a promise — even a murderous one — he kept it.

It’s an early glimpse of the man who would one day cross rivers with armies and rewrite the laws of Rome.

Chapter 2: The Rise of a Political Animal

If Julius Caesar had only been a soldier, history might have remembered him as just another general. But Caesar was something more dangerous: a master of words, charm, and political maneuvering. Before he marched armies across rivers, he marched his way into the hearts (and pockets) of Rome’s citizens.

A Young Noble in a Dangerous Rome

Rome in the first century BCE was a city buzzing with ambition, scandal, and corruption. Senators squabbled like children fighting over marbles, mobs rioted in the streets, and powerful men bought influence with sacks of coin. Into this shark tank stepped young Caesar, from an old but not particularly wealthy patrician family.

He had one major advantage: charisma. Caesar wasn’t just clever, he was magnetic. His speeches dripped with passion, and his presence commanded attention. Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator, once warned a friend: “He is charming, he is witty, he is gracious; but mark my words — he is dangerous.”

Climbing the Ladder

Caesar began working his way through the cursus honorum — the official ladder of Roman political offices. But where others slogged, Caesar sprinted. He aligned himself with the populares faction — the politicians who claimed to fight for the common people, against the aristocratic optimates. This was a clever move: in a city where the masses were restless and hungry, siding with the people meant building a loyal fan base.

He served as a military officer, showing bravery in the field, then dazzled the courts as a lawyer, exposing corruption with fiery rhetoric. His cases weren’t just legal battles; they were performances. Crowds flocked to hear him speak, to watch him tear apart opponents with wit as sharp as any sword.

Money, of course, greased the wheels of Roman politics. Caesar borrowed heavily to fund games and feasts, dazzling the public with spectacles. It was risky — he often teetered on the edge of financial ruin — but it bought him something more valuable than wealth: popularity.

Friends, Enemies, and Rumors

Rome loved a good rumor, and Caesar was often the subject. His stylish clothing, well-kept appearance, and alleged affairs (including whispers about a scandalous relationship with King Nicomedes of Bithynia) gave his enemies ammunition. The optimates sneered at him as a playboy, a pretty boy in politics. But those who underestimated him soon regretted it.

One story tells of a statue of Alexander the Great that Caesar once passed. At the same age, Alexander had conquered much of the known world, while Caesar had only debts and speeches to his name. Caesar wept, ashamed at how little he had accomplished. That moment, historians suggest, lit a fire in him — ambition turned into obsession.

A Reputation Is Born

By his thirties, Caesar had already become a rising star of Roman politics: popular with the people, feared by rivals, and admired by allies who recognized his potential. He hadn’t yet commanded legions or rewritten history, but the pieces were falling into place.

Caesar was no longer just a clever noble with debts and charm. He was a man to watch. Rome, though it didn’t know it yet, had a storm on the horizon.

Chapter 3: The Pact of Giants – The First Triumvirate

By the late 60s BCE, Julius Caesar had earned a name in Rome: charismatic, ambitious, heavily in debt, but rising fast. His fiery speeches and generous games won him friends among the people, but to climb higher, he needed something more than charm. He needed allies. And not just any allies — the kind who could tilt the balance of Roman politics itself.

At the time, two men stood taller than anyone else in the Republic:

Pompey the Great — the golden boy of Roman military glory. He had cleared the seas of pirates in record time and added vast new provinces to Rome’s empire. Veterans adored him, and so did the common people.

Marcus Licinius Crassus — the richest man in Rome. His fortune came from shrewd (and sometimes shady) business deals, including buying up burning buildings on the cheap. If wealth was power, Crassus was practically a one-man bank.

He was Caesar, not only among men, but among fortune’s favorites.”

— Cicero, Roman statesman, in praise of Caesar’s luck and destiny.

The two men disliked each other. Pompey thought Crassus was greedy; Crassus thought Pompey was arrogant. Their rivalry paralyzed Roman politics. Caesar, ever the opportunist, saw an opening: if he could unite them, he could ride their combined power straight into Rome’s highest offices.

The Deal Is Struck

In 60 BCE, Caesar brought Pompey and Crassus to the table. He promised to act as the glue holding them together. Each man got what he wanted:

Pompey wanted land for his veterans.

Crassus wanted financial reforms that favored his business allies, the consulship — Rome’s highest elected office — and a prestigious military command afterward.

This wasn’t a formal alliance. There were no official documents, no Senate approval. It was a backroom deal, sealed with ambition. Later generations would call it the First Triumvirate — the rule of three men.

A Roman historian, Plutarch, wrote that this pact “overthrew the Republic as a storm overthrows a ship.” To the Senate, it looked like three wolves sharing the same pasture. But to Caesar, it was the ladder to power.

The Consulship of Chaos

In 59 BCE, Caesar became consul. Officially, a consul was supposed to serve the Republic with dignity, working alongside the Senate in harmony. Caesar had other ideas.

He rammed through laws granting land to Pompey’s veterans and easing Crassus’s financial burdens. The Senate fumed, but Caesar pushed harder, even having Pompey stand guard in the Forum with soldiers to “encourage” votes.

One senator, Bibulus, tried to oppose him. Bibulus was supposed to be Caesar’s co-consul — Rome always had two to balance power. Instead, Caesar sidelined him completely. Jokes spread that the year wasn’t the “Consulship of Caesar and Bibulus,” but simply the “Consulship of Julius and Caesar.”

Marriage and Maneuvering

Caesar also cemented the alliance with family ties. He married off his beloved daughter Julia to Pompey. It wasn’t just politics — by most accounts, Pompey and Julia genuinely adored each other. This bond made the Triumvirate even stronger, though it also tied Pompey’s fortunes personally to Caesar’s.

A Step Toward Empire

When his consulship ended, Caesar secured his prize: command in Gaul. For the next several years, he would wage the campaigns that turned him into a living legend. Meanwhile, Pompey and Crassus watched from Rome, uneasy as Caesar’s star rose higher and higher.

The First Triumvirate wasn’t meant to last forever. It was built on fragile ambition, and ambition has a way of turning friends into enemies. But for now, Caesar had outplayed everyone. He wasn’t just a rising star anymore — he was blazing across the Roman sky, and no one could ignore him.

And so ends Part 1 of our journey through the life of Julius Caesar. From his daring youth to his dramatic fall, we’ve seen the man behind the legend. But the story doesn’t finish here—Caesar’s death was only the beginning of another chapter in Rome’s history. Stay tuned for Part 2